For over 30 years, Education Evolving has asserted and demonstrated that to make learning more personalized, student-centered, relevant, and engaging, teaching professionals—who know and understand individual student and community needs—should have much larger roles as designers and decision-makers in schools. We now know of over 110 schools in 18 states where teachers do have these larger professional roles, and their network is growing. We call them teacher-powered schools.

And while the visibility of the model is increasing (we’ve tracked over 500 articles in media and blogs over the last several years), misunderstandings persist. The two most common ones are that teacher-powered schools do not have principals, and that all decisions are made by the full teacher group coming to consensus.

In practice, that’s not the case. Most teacher-powered schools do have principals, who often see their role as helping to facilitate shared purpose and collaborative leadership among the team or running interference against outside mandates. And most teacher-powered schools distribute decision-making among committees, grade-level teams, or leadership teams rather than making all decisions as a full group.

Most importantly, there is no single “true” or “best” teacher-powered model. Each school has defined their own roles for leaders, structures for committees and teams, and processes for making decisions. To explain this further, let’s break down the definition of teacher-powered.

Autonomy Is Secured by the School Site, Then Shared

We classify schools as teacher-powered if their teacher team has “collective autonomy” to make final design decisions in at least one of fifteen areas. Those autonomy areas include things like determining the learning program, setting the budget, hiring colleagues, deciding the daily schedule, etc. Among the schools in the teacher-powered inventory, there is a wide spectrum in the level of autonomy; the fewest number of autonomies a school has is four, while some have all fifteen.

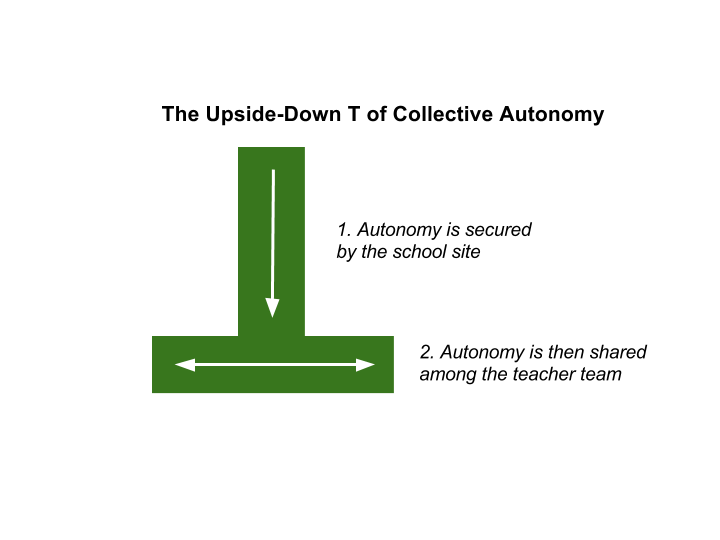

Collective autonomy is a two-part concept. It involves both securing autonomy at the school site and then sharing that autonomy among the teacher team. We have long invoked the image of an “upside-down T” to describe these two parts.

It’s relatively easy to picture part one, where autonomies flow to a school site—for example, to imagine how curriculum decisions might be made by the school rather than the district central office. Part two is more nuanced, and is the topic of the remainder of this post. There are at least three forms of collaborative leadership that teacher teams use to share autonomy, described below.

Three Forms of Collaborative Leadership Used to Share Autonomy

1. Direct—where teachers make most decisions as a full group, usually in a regularly scheduled gathering, such as a weekly staff meeting. The decision making approach within the group is either by consensus or by a vote (with a predetermined percentage—for example, fifty percent or two-thirds—required for action).

2. Distributed—where most decisions are made by subgroups of the full teacher group, usually called “committees” or “teams.” Teachers usually divide themselves up into committees or teams—either by grade level or subject in which they work, by being elected by the full group, or by volunteering. Each committee or team has decision-making authority in a defined area.

3. Representative—where there is a leader (such as a principal), leaders, or leadership team, who often assume their position either by being elected by the full group or by volunteering. Leaders have decision-making authority in a defined area, but are charged with making decisions consistent with the full teacher group’s shared purpose and values.

Different Forms for Different Decisions

In practice, teacher teams use different forms of collaborative leadership for different autonomy areas. For example, school discipline policies may be drafted primarily by the elected leader or principal (representative); hiring and firing decisions may be done by a personnel committee (distributed); and the learning program may be designed and decided on by the full teacher team at staff meetings (direct).

Teams also often mix several forms of collaborative leadership within a single autonomy area. For example, the school budget may be hashed out and decided upon originally by a finance committee (distributed), but then reviewed and approved by the full team at a staff meeting (direct). The full teacher group often delegates decisions in an area to a leader or committee, but retains the ability to intervene if they are uncomfortable with the decisions being made.

Here are some real life examples of these three forms, and the ways they are mixed:

- UCLA Community School in Los Angeles, California has an Instructional Leadership Team (representative), which is made up of three administrators—including the principal and the chairs of eight school committees. The committees (distributed), which include five subject areas for middle and high school as well as three “dens” for the primary grades, make curriculum and assessment decisions. There is also an Operations Team, which makes decisions about scheduling, events, staffing, and hiring.

- Reiche Community School in Portland, Maine distributes responsibilities between a Leadership Team (representative), and four other committees—including Instructional Leadership, Professional Development, Enrichment, and School Climate (distributed). The Leadership Team is made up of three lead teachers who work part-time in the classroom and part-time on administrative tasks, as well as the chairs of the four other committees, two parents, a district office representative, and a union local representative. All teachers serve on at least one of the five committees.

- Avalon School in Saint Paul, Minnesota makes most major decisions as a full teacher group (direct), though they also have specific committees—including Strategic Planning, Personnel, Special Education, and Technology (distributed), as well as three teachers in part-administrator roles as Program Coordinators (representative).

Ultimately, all teacher-powered schools use their own hybrid design for collaborative leadership. There is no “one best way” or “truest form” of teacher-powered. Rather, teacher teams find the mix that works best for their school and for the students and communities they serve. That process of exploration and iterative design—even for the structures and processes of collaborative leadership itself—is what teacher-powered is all about.

Found this useful? Sign up to receive Education Evolving blog posts by email.

This post first appeared in Rick Hess’ blog for Education Week, Straight Up.