This post is part of a larger blog series this year, looking at how schools have used student-centered strategies to respond to the pandemic. This includes both learning designs, but also the success indicators schools use to know whether they are successful. Here, we profile the Spring Lake Park public school district in Spring Lake Park, MN.

When Covid-19 upended regular life, it brought with it a new vocabulary. Social distancing, community spread, “flatten the curve.” The most notable entry to the lexicon in education was “distance learning.”

But not in Spring Lake Park.

The suburban Minnesota district, located a stone’s throw from the Mississippi River a few miles north of Minneapolis, made the sudden move online in March 2020 along with most schools. But instead of “distance learning,” a phrase associated with separation and isolation, Spring Lake Park Schools (SLP) chose a name for remote school that evoked opportunity and ingenuity: “extended flexible learning.”

This simple distinction is indicative of the mindset at SLP — focused on solutions, not problems — championed by the district but buoyed by its teachers, support staff, students, and families.

“We’re going to try it, and if it doesn’t work we’re going to learn something from it,” said Hope Rahn, Director of Learning and Innovation in the district, on the benefit of SLP’s design thinking mindset and methodology, especially during the pandemic.

The district calls its methodology for bringing innovation to practice “SLP3D” (the three Ds being discover, design, and deliver). It’s an iterative process of continuous improvement, assessment, and learning undertaken by classroom teachers and school and district staff together. According to staff, SLP3D ensures they aren’t afraid to entertain new ideas to improve student learning. And it guides almost every decision they make.

Using SLP3D, the district has transformed its physical spaces and students’ learning experiences over the past several years. When the pandemic arrived, it threatened to halt the district’s progress. Instead, it accelerated it.

Going in with a head start: Responding to Covid-19

In the 2020-21 academic year, the learning models across the district and within each school — be they remote, in-person, or hybrid — fluctuated with the conditions of the pandemic. But SLP staff were already primed to try new ways of personalizing learning.

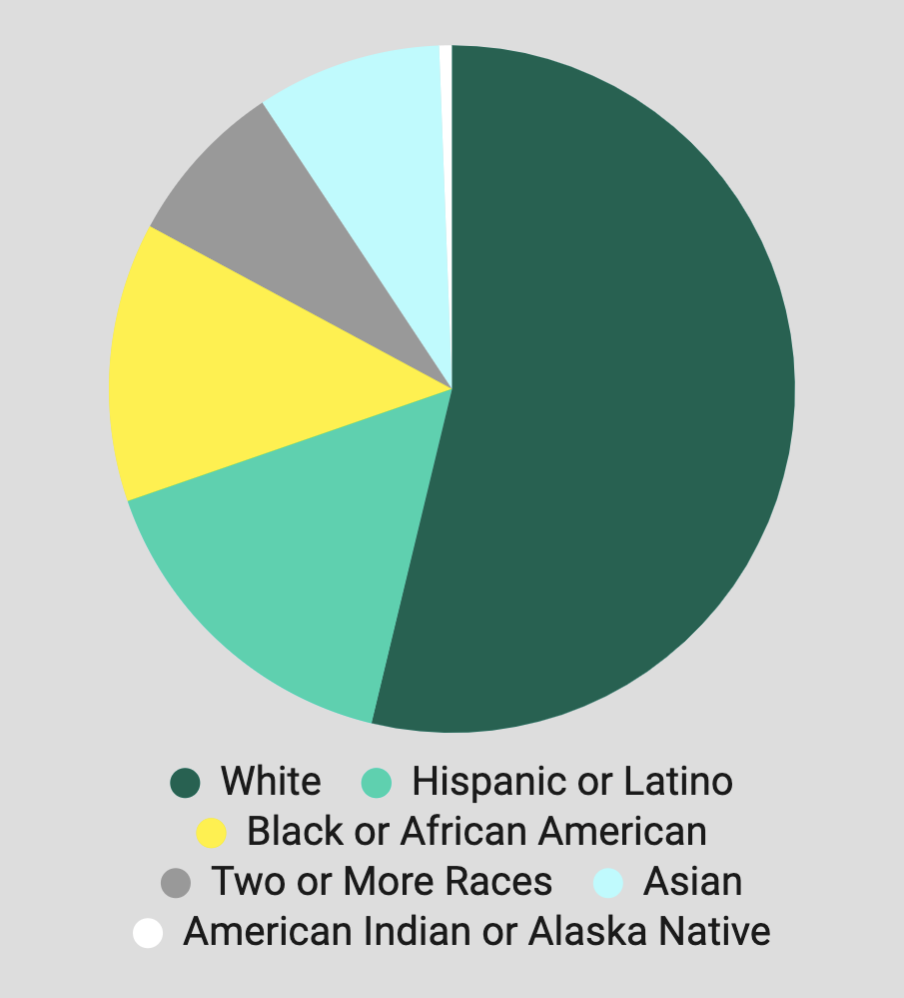

Spring Lake Park Schools At A Glance

Location: Spring Lake Park, MN

School type: District

Opened:

Grades served: PreK-12

Number of students: 6,169

Special Education: 13%

English Learners: 11.6%

FRPL Eligible: 32.2%

This district for years had been 1:1 with iPads, with teachers and students already familiar with Schoology, easing quick transitions when it came to technology. And for a year and a half before the pandemic, staff and teachers had employed a cut, keep, create approach for scrutinizing ideas for learning that should stay, go, or which still needed to be developed.

In June 2020, SLP superintendent Jeff Ronneberg invited any teacher from the district to join a design thinking, innovation cohort. Fifty teachers participated in the process to set a three-year vision for what school could be “if they got to start over.” The cohort began as a response to the pandemic, but such cohorts are a mainstay in the district — a venue where teachers and staff employ SLP3D to reimagine student learning.

“[Ronneberg] said, ‘We’re never going back to fall of 2019 even if Covid is cured tomorrow,’” in prompting teachers to consider greater possibilities, according to Melissa Olson, District Lead for Learning and Innovation. The process helped set the stage for a year with ever-changing learning models, new methods for assessing student learning, and challenging restrictions to keep students safe and healthy.

“How amazing that we’ve done all this work leading up to this [that] is going to help us through the pandemic and ensure learning for our kids,” Rahn reflected on the district’s preparedness. “Has it been perfect? Of course not,” but Rahn credits the hundreds of SLP teachers who dove headfirst into the unknown for what some in the district call their most innovative year.

Principle 1 in Practice: Students finding confidence through competencies

Starting in summer 2019, a previous innovation cohort of 35 teachers convened to establish the district’s first set of competencies, performance indicators, and rubrics for competency-based learning.

Competencies are clear and measurable learning outcomes mapped to academic standards set forth by the state. More than discrete knowledge and skills (like standards), competencies are higher level characteristics of successful learners developed (and still being refined) by SLP teachers.

In a pandemic, SLP teachers viewed the implementation of competency-based learning as a necessity, not as an extra hurdle, because it enabled students and teachers to stay nimble and on-target amongst disruption from shifting learning models. Jennifer Haviland helped pilot competency-based learning for the district with her high school juniors in English language arts.

Haviland told stories of students who found confidence and motivation in competency-based learning where traditional classrooms would have left them discouraged.

One student spent time at a treatment facility during the year, and returned to school stressed about all she needed to make up. Haviland, the student, and the student’s mother met to form a plan.

When the student realized she could demonstrate her competencies in upcoming units — that missing school to access the care she needed did not double her workload or preclude her from deeper learning, but merely shifted when and how she would attain and showcase that learning — “there was an enormous sense of relief,” said Haviland. “She was a great student who happened to struggle with anxiety and depression and it made her feel like [catching up] was achievable.”

At SLP, competency-based learning lets students set the pace of their learning while deepening their ownership and understanding of it. “They can tell you their strengths and areas they need to improve on,” Haviland said. “Competency-based learning has helped us and has helped students identify their gifts.”

Principle 1 in Evidence: Tracking the whole student

Competencies at SLP are grade-banded (K-2, 3-5, 6-8, 9-12), with approximately 6-8 competencies per content area. Within each competency are more descriptive performance indicators that students demonstrate to meet that competency. Competency rubrics list multiple performance indicators and four levels of progression students meet: beginning, in-progress, proficient, and extending.

Students, meeting one-on-one with teachers to set self-paced targets, get to know these rubrics along with models of how they might demonstrate their mastery of competencies.

A question SLP teachers came back to at every learning model shift: What are the most critical learning outcomes of your course? Teachers had to be judicious and hyper-aware of these outcomes in order to navigate the transitions.

Some teams are moving full steam ahead going competency-based, while others are working more on defining the key learning outcomes for a particular course as a stepping stone in that direction. The teachers piloting competency-based learning spent the year in a “cycle of use.” This summer, they’re in a “cycle of work” — refining the standards for the upcoming year.

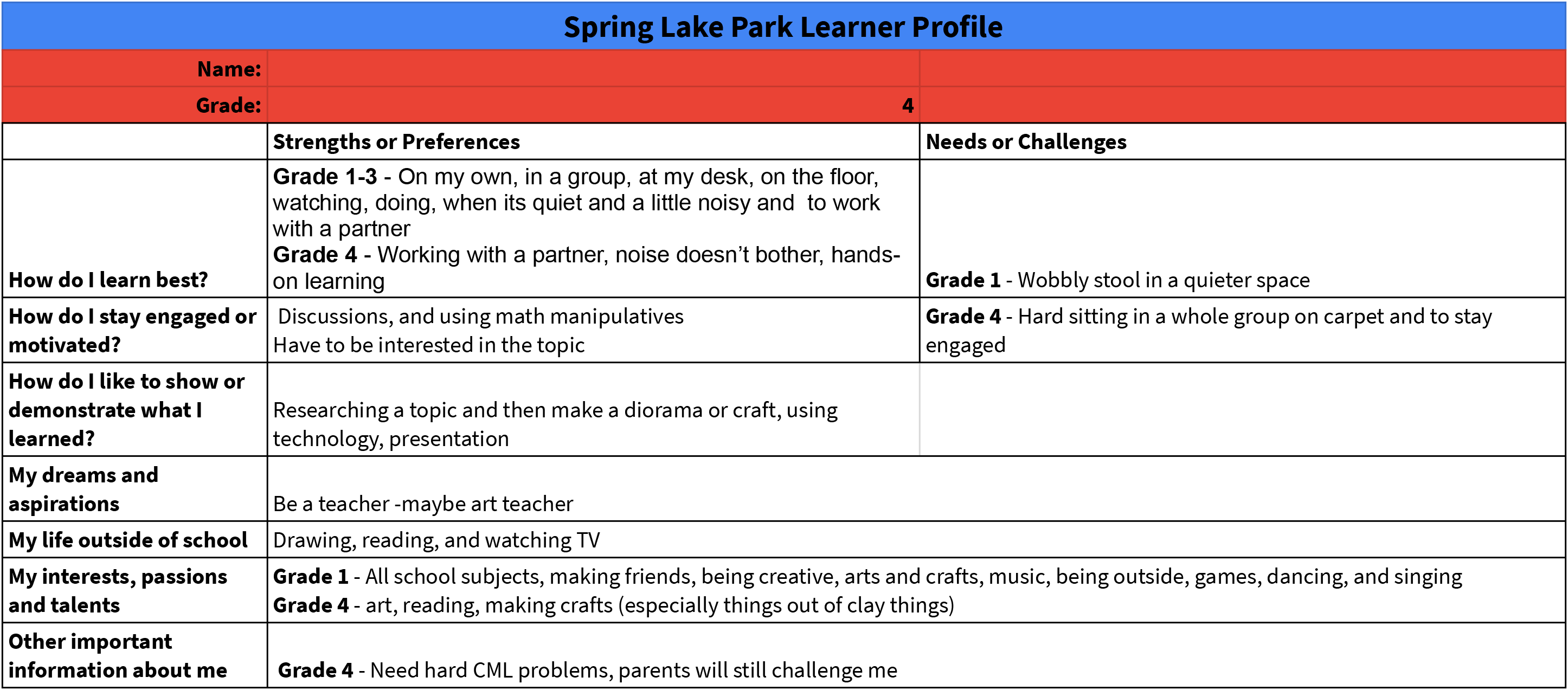

Teachers, students, and parents also use learner profiles and learner maps — living documents to track where students are.

Learner profiles are written by the students themselves, designed to help adults know them deeply. They list students’ strengths and preferences, needs and challenges, and ask probing questions that students are responsible for answering: How do you learn best and stay engaged? What is your life outside of school? What are your dreams and aspirations; your interests, passions, and talents?

This year about 91 percent of students added content to their learner profile that could be embedded into their learning experience.

Another tool in heavy use, the learner map, resembles a competency rubric. On learner maps, teachers and students identify goals together, select learning outcomes, and determine how those outcomes will be demonstrated. But goals need not be content-related; they might instead be set around a student’s social-emotional learning and development, for instance.

Both learner profiles and learner maps had been in use in the district for years but saw wide scale implementation this year because, unlike a traditional gradebook, they tracked how students were doing on a personal level — necessary for keeping connected and personalizing learning in a pandemic.

Principle 2 in Practice: Anytime, if no longer anywhere

Spring Lake Park is an exemplar for “anytime, anywhere” learning — student flexibility around when and where they learn — in large part due to its flexible learning environments, which were reimagined and developed by SLP teachers starting in 2015. More than just striking and beautiful physical spaces, the district’s versatile accommodations adapt to innovative ways of teaching and learning.

Many classrooms have retractable walls to expand the learning space and offer more choice for students and staff. Conference rooms are smaller workspaces for student collaboration and are often used for audiovisual production. “The Great Hall” is a large flex area where classes can be combined and co-taught.

Outside their dynamic school sites, students engage in partnerships with other schools, local businesses, and community organizations on school projects with real-world relevance. Students in the teacher education course work with elementary EFL teachers. Marketing and entrepreneurship students pitch ideas to local companies and had a virtual “shark tank” competition with business community partners as judges. Students in Opportunities in Emergency Care earn Nursing Assistant-Registered and EMT I and II certifications.

Covid disrupted all that.

Even when students weren’t learning from home, the district needed to be able to contact trace, keep students socially distanced, and reduce opportunities for viral spread in each school. Going “anywhere” had gone by the wayside. But not all was lost — as restrictions forced creative solutions.

At the district’s only high school they piloted “teams” for grades 9 and 10. Groups of 150 students in these grades were anchored to teacher teams composed of four core content area teachers and a counselor. Instead of potentially switching teachers each trimester, 9th and 10th graders kept the same teachers all year.

The experiences of these teams — and the wraparound support it afforded teacher teams and students alike — gave way to the idea of Support and Enrichment Time (SET). During SET, a student might request a one-on-one with a teacher, or the other way around.

SET wasn’t the only change to the high school schedule. Staff made time in the afternoons for check-ins with students and families together. And 11th grade English language arts, for instance, was offered nine times during extended flexible learning — at every period of the day, over the lunch hour, right after school at 3 o’clock, and finally at 7 p.m.

The flexible schedule meant many students would choose to come to class at the same time as their friends. This actually proved helpful — breakout rooms were more likely to see cameras on and discussions buzzing as students were comfortable with their self-selected classmates. Many preferred this format to in-person classroom discussions.

Jennifer Haviland and her colleagues knew that each student’s experience of the pandemic was different, and there could be countless reasons regular class times might not work for young people’s newly irregular lives. In addition to that, “I always had video lessons available if [students] missed a live lesson,” said Haviland.

Principle 2 in Evidence: “Learning is the constant, not time”

The new emphasis on competencies, as well as keeping the flame lit on “anytime, anywhere” learning, meant a rethinking of traditional assessments.

Many high school courses didn’t assign grades by trimester, but waited until the end of the year. The district intentionally took a “do no harm” approach to grading — they did not fail students but instead used moments when students were struggling to ask, “Where are you in the learning and what do you need?”

Instead of assigning an F letter grade, the district used “Not Yet.” Where an F has a finality to it, “Not Yet” requires a plan. How is this student going to get where they need to be? They also used NE, or “No Evidence.” A student might have mastery in an area yet needs to demonstrate it.

SLP’s halting of punitive letter grades and grace in giving students time to prove their skills and knowledge shifted the entire student experience.

“Learning is the constant, not time,” said Hope Rahn, repeating what is almost dogma at SLP.

The evidence suggests the experiment was a success: Jennifer Haviland’s English language arts course, for example, saw passage rates on par with non-pandemic years.

Conclusion

Spring Lake Park has no intention of reversing course.

“Our staffing prototypes are more innovative than they’ve ever been,” said Melissa Olson. In addition to maintaining the team structure in ninth and tenth grade, the high school is introducing co-created courses for students interested in growing their competencies and building a course in partnership with a learner advocate. They’re also likely to keep Support and Enrichment Time.

Anytime, anywhere and competency-based learning — both in the works pre-pandemic but stress-tested and piloted in new ways because of Covid — are also here to stay.

Concluded Olson, “Everone’s really excited to keep building and innovating on all the things we had to do this year because we had to do things differently.”

About This Series

This blog post is part of a larger series exploring the practices and success indicators used for student-centered learning in a pandemic—and beyond. We are grateful to the Leon Lowenstein Foundation for their generous support for this series.

Read More & See Other Posts