The word “innovation” is in vogue. Back in March, during our committee testimony on the Innovation Zone bill in the Minnesota Senate, I used the term myself. But what does it really mean? Is it synonymous with “invention,” or does it include spreading existing ideas? Is it about creating new schools, or about improving what’s being done? To clarify this sometimes fuzzy term, and to explore its role in the strategy for improving public education, I offer here a definition.

Most fundamentally, “innovation” means doing things a new way. At Education Evolving, we assert that much of the disappointing performance we see from public education stems from an outdated, industrial-age design of school. Learning experiences could be redesigned to be far more relevant to student interests and career paths, personalized to their aptitudes and abilities, and responsive to their culture and identities.

To dig a little deeper with this definition, I’ll describe four main dimensions of the term below, each of which can be measured along a spectrum from “Type A” to “Type B.” Together these four dimensions offer insight into education policy’s strategy for an equally in-vogue and fuzzy term, “going to scale,” which I will address in the last part of this post.

Four Dimensions of Innovation

Dimension 1: What is the extent of the newness?

- Type A: Fundamental redesign means adopting drastically different designs for learning. For example, using iPads for interactive math games, which adapt as the student is playing based on their abilities and track their progress over time.

- Type B: Incremental improvement means making adjustments or tweaks at the margins, without fundamentally changing the design of school. For example, using iPads to read traditional textbooks.

Dimension 2: Has the new ever been done before?

- Type A: Invention is creating new designs from scratch. This doesn’t mean new designs must come out of thin air; invention often includes combining existing design elements in new and different ways. Innovation as invention means “new anywhere.”

- Type B: Replication is the process of spreading inventions, which were once uniquely new and different, to another school. Innovation as replication means “new here.”

Dimension 3: Is the school itself new?

- Type A: Creation means implementing a new design in a totally new school or program. For example, a group of teachers and parents coming together to create a new experiential learning school in the charter or district sector.

- Type B: Adoption is about converting or refining design characteristics in an existing school or program. For example, teachers at a traditional school decide to set aside all Fridays for experiential field trips. Or, a school “restarted” under NCLB adopts a totally new curriculum model.

Dimension 4: Who initiates the new?

- Type A: People at the working level create designs based on the individual needs of the students those designs will serve. For example, at teacher-powered schools, teacher teams serve as both designers and implementers of the learning program.

- Type B: People in outside support roles, who either recruit people to implement those new designs or pass them on to people already working in schools.

Going to Scale Requires Both “Type A” and “Type B” Along These Dimensions

In practice, innovation occurs at various places along these four dimensions. No innovation is fully, uniquely an invention vs. replicating what has been tried elsewhere. No innovation can be neatly described as fundamental change vs. more incremental. No innovation is fully attributable to people working in schools vs. those outside.

Nor should we place judgement on innovation based on where it falls. To bring new and better designs for learning to scale, we will need both Type A and Type B innovation. That is, we will need both drastic reinventions generated by creative teacher teams in newly created schools, as well as more incremental changes spread through a process of replication and adoption. Type A innovation is not for everyone, and that’s okay.

That said, Type A innovation does perhaps represent a “purer” form of the concept. It embodies the term romanticized in startup culture—the term associated with companies that were launched in garages and went on to become the largest, most influential companies in the world. It is absolutely critical, even as we think about “scaling up”, that our public education system remains open to Type A innovators. We need their hope, energy, and ideas to fuel the other forms of innovation.

Transforming Public Education via Innovation Gradually Spreading

Whether Type A or Type B, the process by which innovation proceeds is extremely important. Education Evolving’s co-founder Ted Kolderie discussed the process of change through innovation in his book The Split Screen Strategy. He cautions that innovation is not something that can be successfully mandated. Policy should create opportunities and incentives for folks to design different and better learning experiences, but not require it.

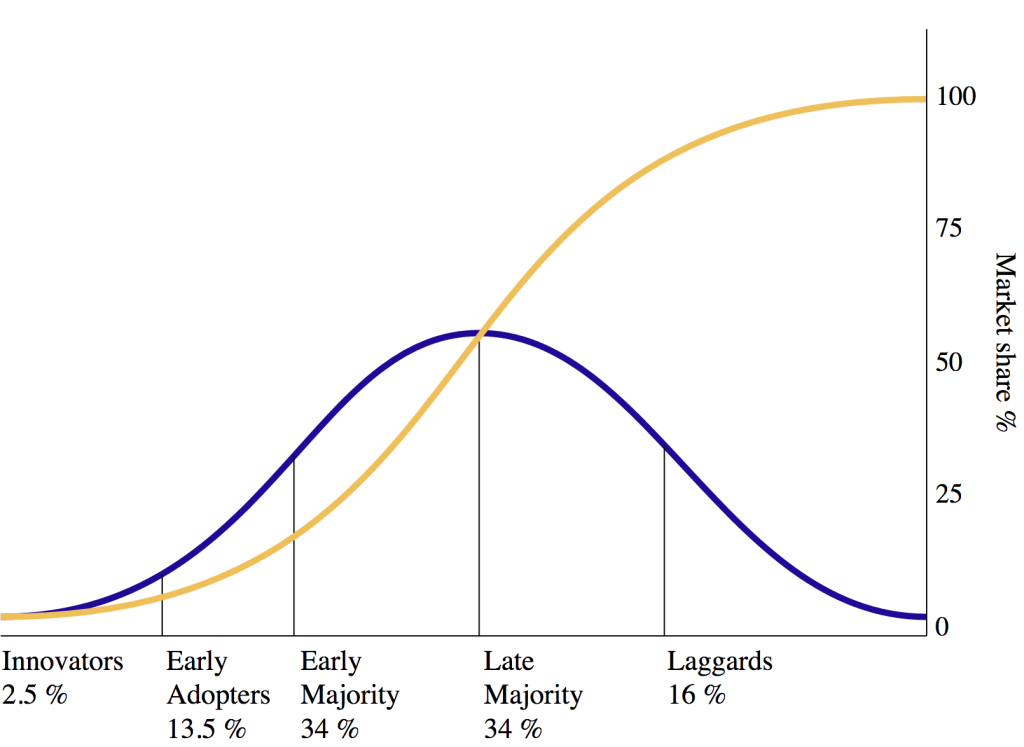

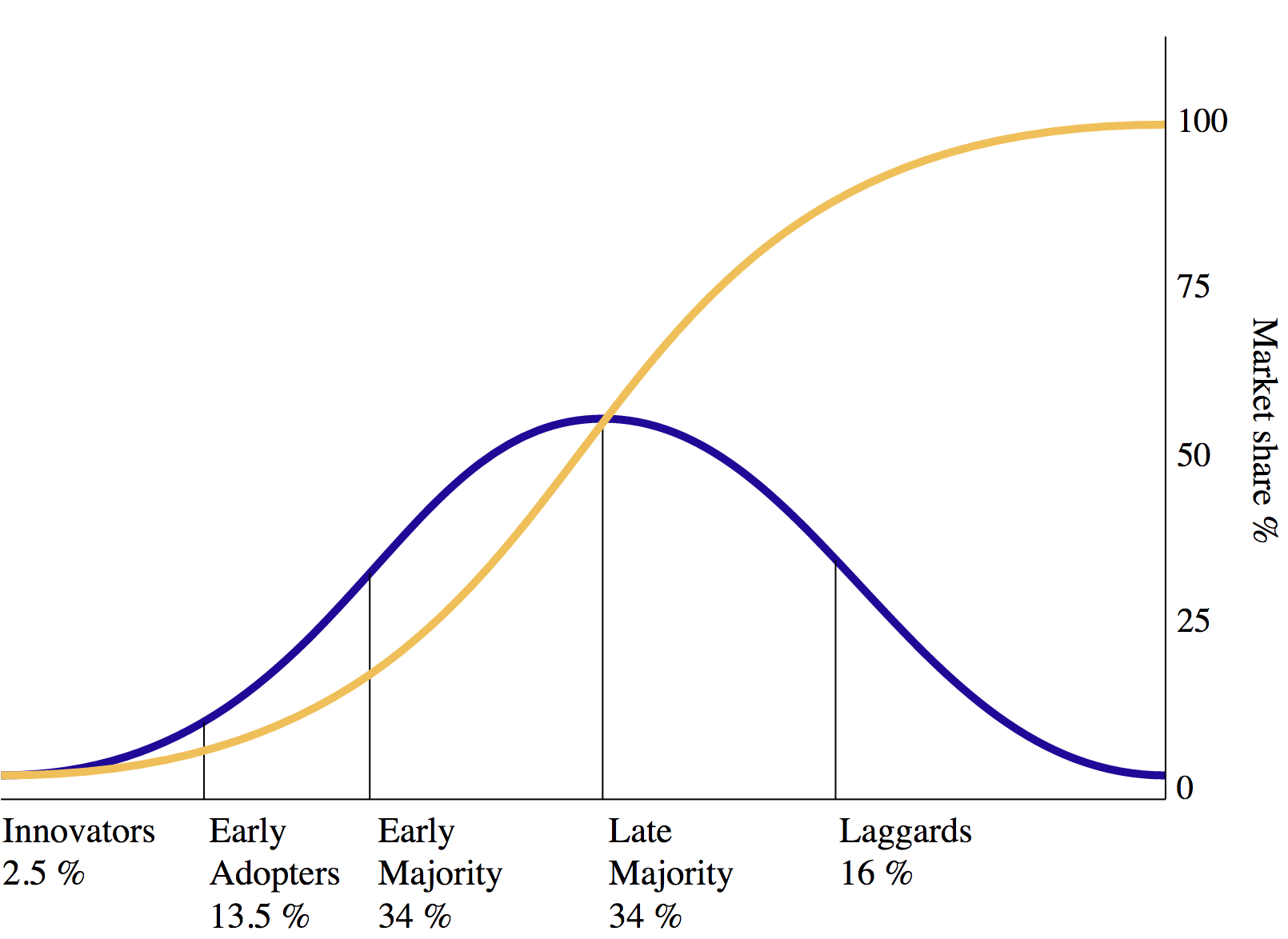

There will be early adopters breaking the mold of industrial age schools, then early and late majority, and, finally, the laggards. Everett Rogers created the now-famous “diffusion of innovation curve” (pictured below) to describe this concept, which is based on his life’s work documenting the social diffusion of new ideas in countless fields. Rogers’ observations corroborate Kolderie’s assertion that “innovation gradually spreading and improving is systemic reform.”

So, let’s keep asking how we can create the conditions for new and different designs for learning to emerge. Let’s do more to spread and replicate the designs that work well. But let’s tolerate and respect—and defend—those working at all points along the spectrum from Type A to Type B. All are needed to help public education through the process of change, so that it can finally meet the needs of all young people.

Found this useful? Sign up to receive Education Evolving blog posts by email.

This post first appeared in Rick Hess’ blog for Education Week, Straight Up.