It’s summer and Park Center Senior High in Brooklyn Park is quiet, half dark. In a few days, teachers will return to ready their classrooms. A few weeks later, students will fill the halls once again. But in Pang Yang’s classroom, there’s a bustle. A group of student volunteers are painting ceiling tiles to add to the decor of the room, its walls already adorned with Hmong imagery: words, art, poetry, photography, history.

This classroom is home to Hmong for Native Speakers, a world language course at Park Center. Students—mostly native speakers who have been English learners (ELs) their whole time in school—also receive bilingual seals and college credit through the course.

“Literacy is a new thing to our people,” says Pang, because “the language was mostly oral until the 1950s.” This makes Hmong a tricky language to teach. There aren’t a great deal of ready materials for students. And there aren’t enough role models; Pang is one of only two Hmong staff members at the school. She tackles this challenge in part by inviting guest speakers from the community to share their personal experiences.

After a fall residency last year with Tou SaiKo Lee, a Hmong hip hop artist, the class published a book, From Mountains to 10,000 Lakes. 40 student poems were selected for the book and five students did all the artwork.

This month, a group Hmong authors from across the country will convene at Park Center for a workshop entitled “Embracing the Love of Reading and Writing”, to help instill in students a love of culturally relevant books and a desire to become authors themselves. It’s about reading, Pang says, but also about storytelling. “If they don’t share their story, someone else will write that story for them.”

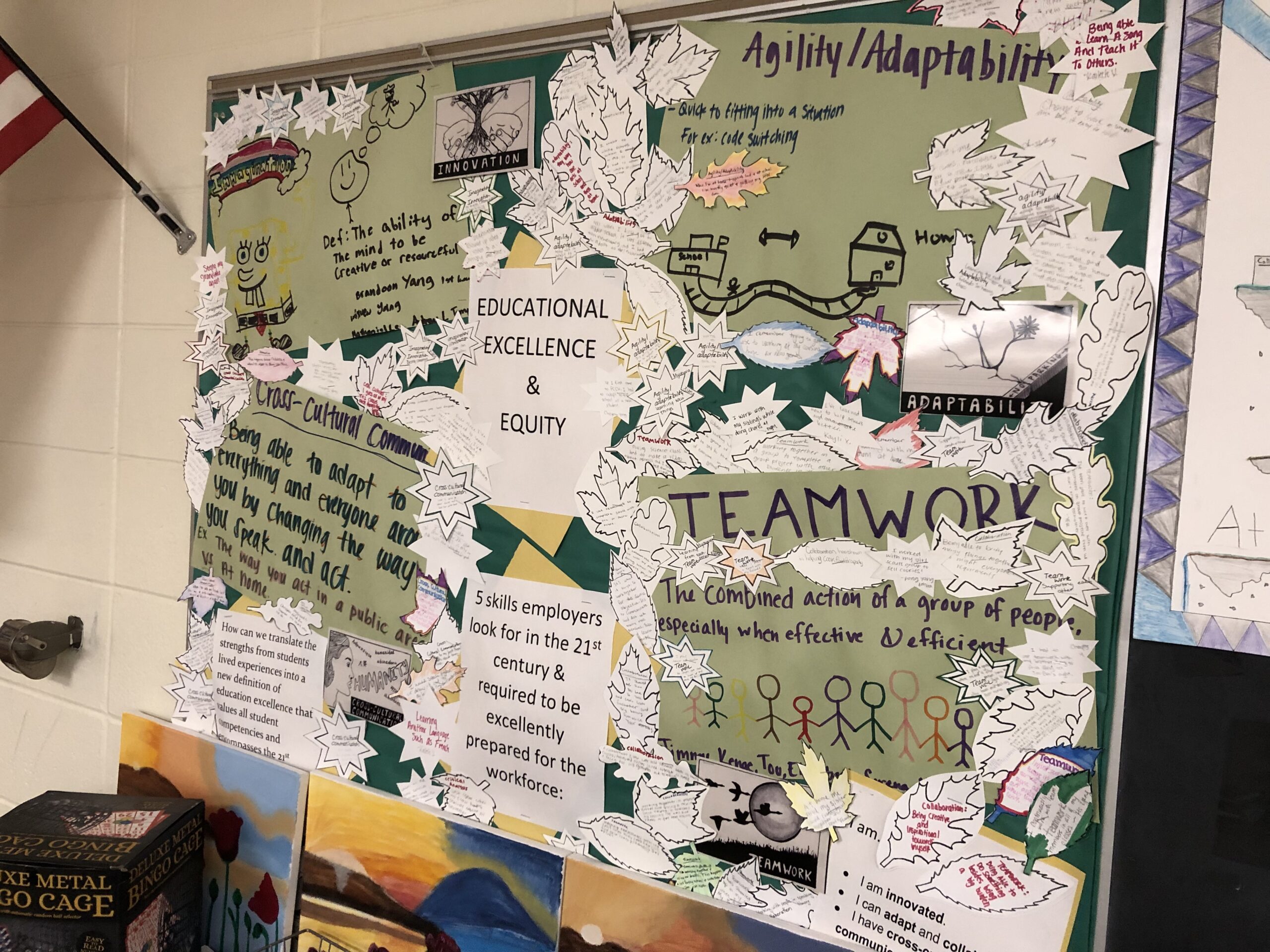

Above all, through an exercise in literacy, the course gets at something much deeper—the exploration of identity. Where do you come from? What’s your history? What’s your family’s history? Students come to know themselves, their culture, their language, and in so doing love who they are. They develop self efficacy through identity.

A course built on relevance and student agency

Hmong for Native Speakers is open to speakers of all levels—novice, intermediate, advanced—who all begin their first year in the course together. The wide range of proficiency has necessitated actively personalizing learning for each student.

First, Pang did away with hour long lectures. Lessons are much shorter—about 15 to 20 minutes—and always interactive and relaxed. There are a few whole group activities, but students are otherwise free to create their own learning path. Whether working individually or in small groups, what matters to Pang is that the students understand and meet the course expectations.

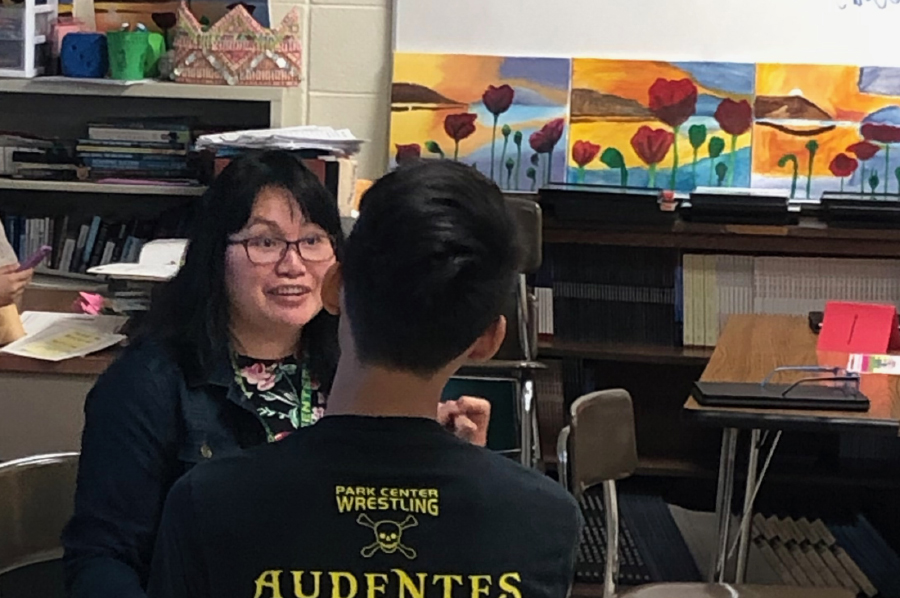

Pang’s students use their most comfortable language in the classroom, be it Hmong or English; novice and intermediate speakers aren’t pushed so hard that they disengage. The students know it’s okay to make mistakes, it’s okay to not know the answers. Pang volunteers that she doesn’t know everything, and that she sees herself less a teacher than a facilitator. “We can all learn together,” she says.

For class projects, students have different options according to their proficiency levels and based on their interests. During a Hmong art unit, students sewed textiles, painted, and performed. One group wrote a song about finding love in the class—lyrics all in Hmong. Pang observed, “Quiet kids come out when given the opportunity to produce something that excites them.”

Pang likes to see her students innovate, problem solve, and above all develop a sense of self efficacy. Student ownership and agency is key to their success, in her view: “I ask students for input about the class—what’s going well, what’s not, what should change. I survey every couple of weeks. Students have a voice in the class.”

“The kids guide [a lot of] what we talk about. I make time to do that, even if it derails us,” says Pang. She also makes time to regularly meet with students one on one, looking at their overall grades and giving them the tools to advocate for themselves, contacting counselors and even calling home to ensure student success. She doesn’t want students without behavior issues, less likely to be ‘noticed’ but who may still be struggling, to get lost in the shuffle.

A course born from student initiative

Pang spent 19 years as an English as a Second Language teacher. She started at Minneapolis Public Schools before coming to Osseo Area Schools, where she’s been since 2003. When Pang began at Park Center, she taught upper level EL courses, collaborating with history teachers for years and even integrating lessons on the Hmong Secret War into a unit on the Vietnam War. It was then the opportunity for Hmong for Native Speakers opened up.

A similar course, Spanish for Native Speakers, was already underway. Hmong students saw the opportunity available to their peers and asked, “What about us?” Pang answered, “If you’re willing to work, we can do anything.”

A group of a half-dozen Hmong students took initiative, organizing several parent meetings and later a large community meeting with parents, students, and important stakeholders like school board members and school department heads. At the meeting, students and parents shared the need for more programs to support Hmong students in Osseo Area Schools, second in the state only to Saint Paul Public Schools for the size of its Hmong student population. They expressed the need for students to discover who they are and develop their identity, language, and culture.

After the meeting, Pang’s principal said to her, “Let’s write a course proposal.” The year after, they wrote a proposal for year two, then year three. Now, nearly 40% of all Hmong students at Park Center are enrolled in the course. Pang has plans to launch Hmong for Native Speakers 4 next year.

An advocate for her students, now and always

Pang’s students and colleagues agree she is a remarkable teacher. But she’s quick to point the spotlight elsewhere. It was her students who made such a passionate case for the course, she was only following their lead. The electric environment in her classroom? See the community members who share their time and expertise and the students who so meaningfully engage. The wherewithal to keep going? Thank the support of her mentors: fellow teachers, the school digital learning specialist, a colleague from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater who Pang counts as her heritage language coach, the Park Center principal. (Incidentally, these people claim no credit. It’s all Pang, they say.)

That principal has noticed some early signs of positive academic outcomes since Hmong for Natives Speakers began, like fewer Fs across courses overall among Pang’s students. They’re watching closely at Park Center to see what they can learn from the data year over year. Pang also looks beyond the years she has the students in class—she maintains supportive relationships with alumni attending college, inviting many to return to her classroom to advise current students navigating toward graduation and life after.

Pang is ever a fierce advocate for her students, always holding their identities, needs, aspirations, and voices at the center. “They need to be heard. They need to be amplified,” Pang says.

We’re listening.