Written by Amy Carlson Gustafson

This post, ‘Retaining Teachers’ Event at Wilder Foundation, was first published in the University of St. Thomas Newsroom and has been re-published here with permission.

With a teacher shortage affecting schools across the nation, the University of St. Thomas School of Education and Education Evolving teamed up to examine what can be done to increase teacher retention and what conditions enable teachers to thrive in their schools.

About 100 people turned out at the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation in St. Paul on Nov. 7 for “Retaining Teachers: Fostering Conditions Where Talent Thrives.” The event featured the University of Pennsylvania’s Dr. Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology and senior research specialist at the Consortium for Policy Research in Education, who discussed teachers leaving the profession at high rates and possible solutions to this issue.

Following Ingersoll, Dr. Kathlene Holmes Campbell, dean of the St. Thomas School of Education, moderated a panel of Twin Cities teachers and administrators who talked about their own experiences in education. The panel included:

- Latanya Daniels ’01 MA, ’04 EdS, ’19 EdD, principal of Richfield High School

- Nafeesah Muhammad, an English teacher at Community Connected Academy at Patrick Henry High School in Minneapolis

- Vanessa McDuffie, a School of Education student in the Minneapolis Special Education Teacher Residency Program, which is a partnership between Minneapolis Public Schools and the University of St. Thomas

- Bao Vang ’06 MA, ’15 EdS, principal of Community of Peace Academy in St. Paul

Teacher shortage

Ingersoll started things off with the question: Why is it so hard to staff our classrooms in the country with qualified teachers?

Conventional wisdom, he said, is that we simply don’t [produce] enough teachers to solve the teacher shortage, leading people to try to devise initiatives and incentives to bring more people into the teaching profession. These initiatives don’t work. Instead of looking at the larger demographic trends, we need to focus more on how schools themselves are operating and functioning. He said the problem isn’t that there are too few people becoming teachers, it’s that too many teachers are leaving the profession.

“The solution can’t simply be to recruit more people. We also have to focus more on retention, teacher turnover, departures, attrition, etc.,” he said.

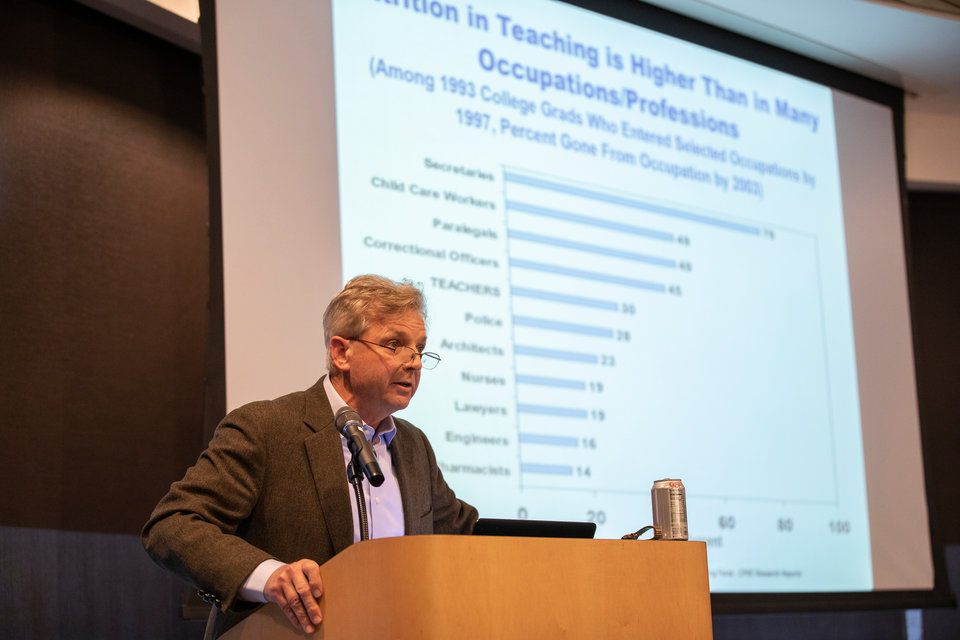

Turnover is a “very big problem in K through 12 education,” he said. Teaching is not only one of the nation’s biggest workforces, it’s also a high attrition profession, surpassing high stress jobs including police officer and nurse. The large workforce and high attrition rates of the teaching occupation lead to a “revolving door,” where nearly a million teachers move into, between and out of schools each year, he said.

This high turnover rate is behind teacher shortages, he said, and it’s very costly. While the rate at which the revolving door moves varies among types of teachers and schools, it affects low-income rural and urban schools at much higher rates than at schools in higher income, affluent districts.

“Why is it, some schools have so much more [turnover] than others? And to me this is a very important question because if we don’t get the diagnosis down, the prescriptions will never work,” Ingersoll said.

Pointing to data from a national survey by the Federal Department of Education of public school teachers across the country, Ingersoll said the three biggest factors driving pre-retirement and voluntary turnover are dissatisfaction with accountability/testing, dissatisfaction with administration, and lack of influence and autonomy.

“In buildings in which teachers had little input into decision-making, an average of almost a fifth of their teachers voluntarily depart each year,” he said. “On the other hand, schools in which teachers had a lot of decision-making input – it was less than five percent.”

So what can be done to slow teacher turnover? Giving them more of a voice when it comes to key decision-making within their buildings, he said. Some state legislatures even have stipulated teachers have more say in their schools. Another idea is to have teacher-run schools following in the model of professional partnerships such as accountants or lawyers, thus giving teachers the autonomy, training and resources they need to be successful while also being held accountable.

“If we can improve some of those conditions in schools, like the issue of voice and input into decision-making, that’s going to slow down – the data tells us – teacher turnover rates dramatically,” Ingersoll said. “That, in turn, is going to help student achievement.”

Educator panel

Following Ingersoll, School of Education Dean Campbell explored the subject of retaining teachers by asking the panel members about their experiences within the educational system.

“This is going to be really powerful to hear from people who are in the schools and are really having to address this issue that I think is probably the most important and pressing issue of our time,” Campbell said.

Campbell asked Nafeesah Muhammad about her autonomy at the Community Connected Academy at Patrick Henry High School. Muhammad said one of the reasons she left her previous school was because she felt her ideas around education had “hit a ceiling.” In her new teaching position, she said she and her colleagues are able to create student-led projects that are culturally responsive and relevant to their students’ lives. She said she feels empowered by empowering the students.

“We’re extremely flexible in reaching the students because we believe education needs to be student-centered,” Muhammad said.

Vanessa McDuffie said when she was a student in the public school system, there were times she didn’t feel seen. She followed her heart and went into teaching so she could become a great motivator and advocate for children, showing them their potential even if they might not realize it themselves.

“I am currently at Pratt Community School. I started as a special education assistant and the principal there, Nancy Vague, really pushed me to consider doing more,” McDuffie said. “She saw that I was on the equity team and she saw that I was always coming to her with a lot of ideas. … She asked, ‘how can we get you further than you are right now?’ I’ve only had a few different teachers and administrators in my life that really saw that. So if I can bring that to the students I work with, it’ll all be worth it.”

When Campbell asked how administrators create an environment in which teachers feel valued and supported, Dr. Latanya Daniels said she strongly believes in teacher voice and leadership in schools.

“I really see myself as a leader, as someone who makes the way for changes in student-centered initiatives to move forward,” Daniels said. “I see teachers who are the No. 1 lever, who would impact student achievement, as the No. 1 partners in ensuring that that happens. I really try to elevate teacher voice and I also try to elevate student voice, to make sure that we have a teacher-centered and student-centered school.”

Answering that same question, Bao Vang said in her role as a leader she thinks about herself being visible, listening and giving voice to her teachers.

“I think it’s super important to listen to teachers about their struggles and then come up with ideas and strategies on how to support them,” Vang said. “And to be OK in that we don’t have to be perfect, because teachers feel like we have to be perfectionists all the time. We have to give permission as administrators to teachers to know they don’t have to be perfect because that is not sustainable.”

Vang added: “I work really hard on listening to the teachers and figuring out what the issues are. How do we come together to solve them because nobody else can solve our problems for us.”

After the audience had a chance to ask a few questions, the evening ended with a reminder by Campbell that teacher preparation standards are currently being revised in Minnesota. She asked those in attendance to write down ideas about what needs to be done differently to prepare teachers to stay and thrive in classrooms.

“Stop and think about what skills you think should be part of teacher preparation programs to make sure that when we’re preparing teachers, we’re preparing them to stay for a lifetime and not one year, three years or five years,” Campbell said. “We want to make sure that they are ready for the classroom on day one, but we also want to make sure that they are thriving.”

Found this useful? Sign up to receive Education Evolving blog posts by email.

We are grateful to the McKnight Foundation for their generous financial support for this series.