This post is part of a larger blog series this year, looking at how schools have used student-centered strategies to respond to the pandemic. This includes both learning designs, but also the success indicators schools use to know whether they are successful. Here, we profile Crosstown High in Memphis, TN.

It’s rare that opportunity knocks while driving down the interstate.

As the creator of the Memphis School Guide, Memphis native and parent Ginger Spickler was disheartened by the lack of compelling options present in her city’s high schools. When she saw a billboard along I-55 advertising the XQ Super Schools design challenge, she organized a meeting of parents, educators, and community members to imagine what a new high school could look like.

After a successful bid for funding from XQ and years of planning, Crosstown High opened to its first class of ninth graders in fall 2018. Crosstown is an innovative charter high school located on the fourth and fifth floors of Memphis’ Crosstown Concourse, a ten-story “vertical village” home to over 40 business and organizations. It is authorized by Shelby County Schools, the public school district in which it’s located.

Amongst Memphis’ elite private schools, traditional public schools, and “no excuses” charter schools, Crosstown offers something unique. Its founders settled on four main design pillars: it would be diverse by design, competency-based, project-based, and relationship-based. Twelve competencies “necessary for success in life after high school” drive instruction.

Crosstown At A Glance

Location: Memphis, TN (urban)

School Type: Charter

Grades served: 9-11*

Number of students: 397

Students with Disabilities: 20%

English Learners: 3%

FRPL Eligible: 49%

*Will add another grade in 2021-22 to serve grades 9-12.

Source: Crosstown High School 2020-21 records

Crosstown’s student body intentionally reflects the city’s diversity. Just over half of students are Black and about a third are White. The remaining 15 percent are Latinx, Asian, Middle-Eastern, or multiple races. Students come from all corners of Memphis.

Taking it day by day: Responding to Covid-19

The reality of Covid hit Crosstown just before spring break. “Our teachers just did a really remarkable job” with the transition, Chris Terrill, Crosstown’s Executive Director, said. “Literally a week after we were supposed to come back from spring break, we were ready to go.”

Students already had one-to-one devices, but staff really embraced technology and went to great lengths to ensure students were accessing rigorous learning opportunities from home.

Teachers were more comfortable preparing asynchronous learning experiences that final quarter—recording lessons and scheduling student work time—but some experimented with live class sessions, too.

Come fall, Crosstown students returned to fully live, virtual class sessions four days a week with “Asynchronous Fridays.” Students maintained a block class schedule with four class periods a day, alternating seven classes and one “flex period” used for a range of engaging activities, like student clubs, guest speakers, and programming for Black History Month.

Toward the end of the second quarter, Terrill began bringing about 20 students to school each day who needed “additional assistance and a safe space to work.” That number grew over the next few months as parents and staff agreed it was in students’ best interest to be at school.

By March, all students had returned to school two days a week on a rotational basis.

Reflecting on the past year, students we spoke to acknowledged it was tough. Tenth grader Shania Lee told us, “I’ve learned to take things day by day and test by test. Sometimes it’s a lot. You have to put things into compartments to move on. And it’s hard to do that being at home, where it’s like, this is your wind down space… Now it’s a lot of spaces.”

Principle 1 in Practice: Cultivating positive relationships through attention and persistence

“We are a relationship-based school,” Terrill responded when asked what sets Crosstown apart from other schools. Positive relationships with students are foundational to teachers’ ability to influence students and hold them to high standards.

Covid has really tested staffs’ relationship-building confidence. One major challenge? The feeling you’re “shouting into a void.” With students’ cameras often off and their microphones muted, it can be easy to doubt whether you’re reaching anybody.

One remedy for Lauren Mueller, an 11th grade English teacher, has been to pepper her live classes with references to individual students to keep them listening and responding. “Sometimes kids get spooked when I remember a detail they told me, about what they’re doing this weekend or something they enjoy,” Mueller said. But her students appreciate the attention she pays to their personal lives. “We love to be seen as whole people, and love to be like, ‘Oh my gosh! You remember that fun fact, Oh, so cool!’”

For some students, building a relationship requires a lot more persistence. Mueller had to invite one student to office hours seven times before he finally showed up. Her tenacity showed the student she cared about him and believed he could improve.

Though educators may value relationship-building with students, schools aren’t always structured to support it. At Crosstown, time for relationship-building is built into the school day. All students are assigned an advisory—a home base of 10-12 students—where they can deeply connect with a single staff member on a regular basis. Students have 10-15 minute one-on-one check-ins with their advisors at least every two weeks.

“A kid may skip an English class from time to time or check out, but they are showing up for that one-on-one time with their advisors,” Terrill said. That is a prized time that they are relishing, just having those conversations.”

The value of one-on-one check-ins was not lost on students. When asked how teachers could ensure students of all backgrounds are learning during the pandemic, tenth grader Arianna Wright’s advice was to always check in on students individually. “Even if you feel as if they are okay, even if you feel as if nothing is going on, you should always check in because you never know what is going on behind the screen.”

Principle 1 in Evidence: Gauging student engagement and sense of connection

Traditional school success measures, like scores on achievement tests, can’t demonstrate to staff how well they’re connecting with students. But those connections drive students to want to learn. That’s why Crosstown teachers and leaders emphasize monitoring students’ attendance and retention—measures that capture how much students want to engage with their teachers and peers.

And they tend to do well in these areas: pre-pandemic, Crosstown was recognized for having one of the highest attendance rates in the district, a pattern that has carried over into the current school year. Few students choose to leave the school once enrolled. Only six of Crosstown’s four-hundred students have unenrolled this year, with only two weeks remaining until summer break.

Further evidence students want to be at Crosstown? Despite the shift to distance learning, the school had another strong admissions season, receiving 235 applications for 135 spots.

When students start to show signs they’re disengaging—like logging in but not responding to a teacher’s questions—there’s a robust system in place to communicate the issue among relevant staff and to problem-solve accordingly.

Advisors use a Google spreadsheet to track advisees’ attendance at their biweekly one-on-one check-ins, taking notes before and after the meeting to document discussion topics and decide next steps. Other teachers can write notes to a student’s advisor, requesting they touch base with the student on something they might be struggling with. The same document is used to guide conversations at weekly grade-level team meetings, where a tiered approach is used to refer students for more intensive, individualized supports.

Another tool teachers use is a Wednesday Wellness check—a weekly five-question Google form that goes out to students asking them how they’re feeling, where they might need assistance (e.g., with mental health, school work, or emotional health), and whether they need to meet with their advisor. Staff use the results to prioritize which students to check in with.

“Our teachers are really paying attention,” Chris Terrill said, acknowledging the effort put toward tracking and following up with individual students. Spickler agreed. “The advisory piece has been really critical because there’s no chance to fall through the cracks. Like, we are chasing you!”

One major benefit to “paying attention” is the motivation students experience when teachers honor the needs and interests they express—the topic of the next section.

Principle 2 in Practice: Promoting student ownership and agency

Crosstown prizes student ownership and agency—the idea that students take responsibility for their learning when their passions and interests are represented in it, and when they have power to advocate for changes that help them and their communities.

As a project-based school, Crosstown students have lots of opportunities to pursue projects that speak to them. Though Covid has limited the kinds of projects students could engage in, there has been no shortage of engaging projects—from reimagining the “I Voted” sticker, to creating a personal fitness website, to producing an original song for the XQ Music and Activism Challenge (Crosstown students won second and third place in the national competition). One student even launched an online soap business.

Teachers listen and respond to student feedback when developing project guidelines, one way students enjoy ownership over their education. Students participate in “project pitch” sessions to ensure the projects they’ll be asked to do will be interesting, engaging, and meaningful. This can be an eye-opening process for teachers.

Sociology teacher Kat McRitchie was surprised when her students vocally opposed a project idea she had pitched to address the continued existence of Confederate monuments in Memphis. She thought the project would land well with students, who cared a lot about combating racism in the community. But students were tired of talking about Memphis. They wanted a broader scope. And firmer deadlines! “As a teacher, I try to plan by thinking about what students are interested in. But I’ve learned I’m not always right. Sometimes, my assumptions are totally wrong.”

Crosstown students want projects to have an impact beyond themselves. Lee described such a project in her environmental science class about threats to a local watershed. Students learned about environmental racism and the disproportionate impacts of pollution on communities of color, and were organizing a meeting with community leaders to discuss what they’d learned and propose solutions. “The end product would basically be a drawn out plan of what the community should look like,” Lee told us. “What environmental resources can we use that won’t harm? How can we engage the residents? How can we build this project to serve the community?”

Principle 2 in Evidence: Students documenting and presenting their learning

As Crosstown’s Project Curator, Danielle Tyler has worked over the past year to build out systems and processes to document evidence of students’ learning, guide students through the iterative prototyping process, and provide formative feedback on student projects through self-reflection and peer evaluation.

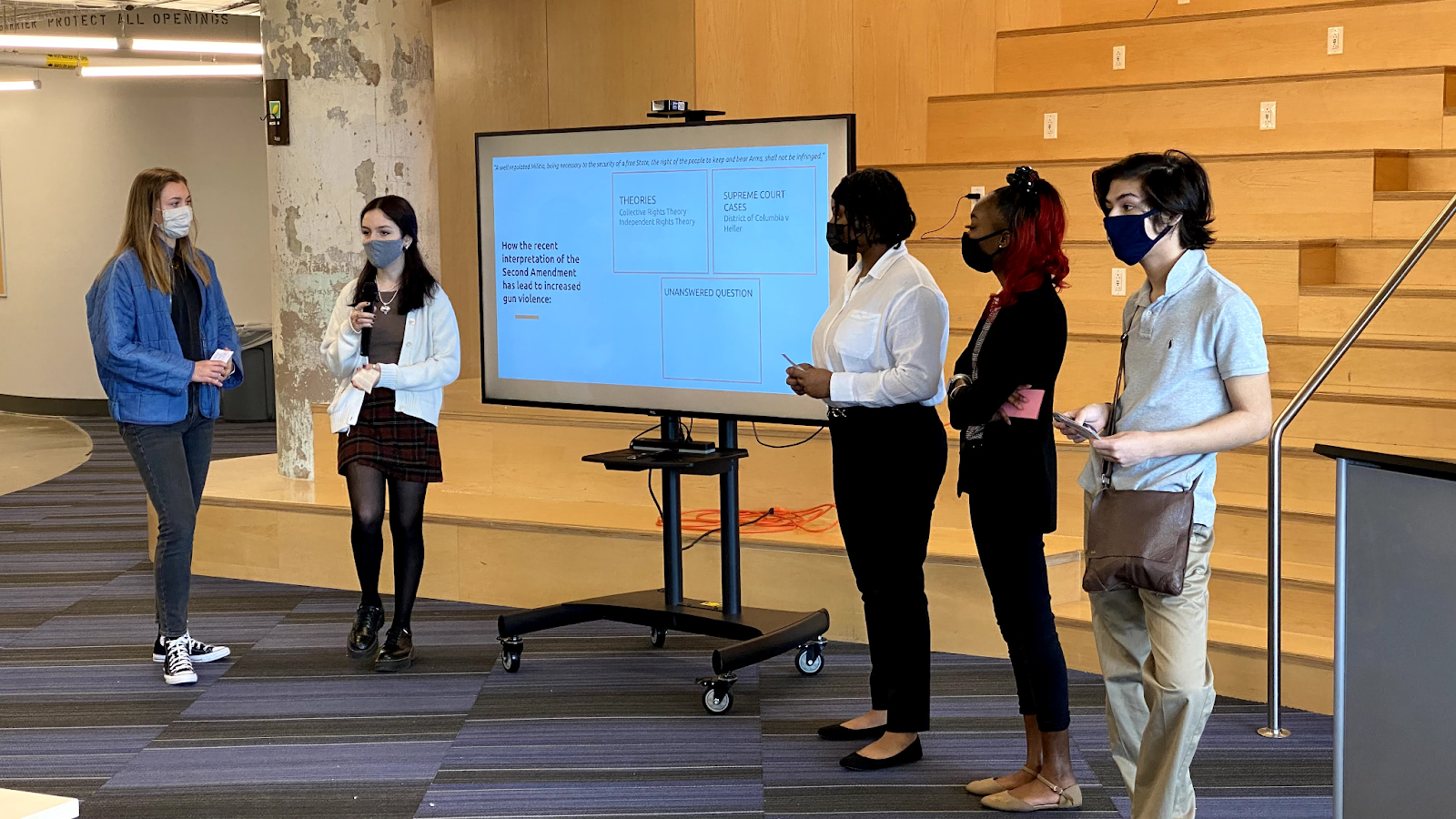

This year, Tyler hosted a virtual “Prototype Fair,” a multiple day, online event open to all Crosstown students and teachers during which students—individually and in groups—presented works in progress for critical feedback. Students provided input on their peers’ projects using a “TAG” protocol submitted through a Google form: tell the presenter something you like, ask them a question, and then give them suggestions for improvements.

Tyler has been encouraged by the opportunity Covid has presented to use technology to document the project process. “With the pandemic, everything is online. There is always a history in Google Docs and Google Drive about how you came to this product.” Those features have helped students to see and appreciate how their work has evolved, or where they might have gotten stuck along the way.

Teachers are also experimenting with competency-based grading, which lends itself to a student-centered, project-based curriculum. Mueller, for example, devised a “Competency & Task Tracker” document in which students self-assess their learning on Crosstown’s 12 Core Competencies as they complete assigned tasks. Students must provide data or other evidence to support their ratings—developing, approaching, mastery, or exemplary—in the right hand column of the document, as shown below.

Crosstown staff are now establishing student assessment practices that don’t just assign students a score or letter grade for completed assignments, but encourage reflection and revision of meaningful work. Involving students in their own self-assessment helps them see their progress and encourages them to take ownership of their learning.

Conclusion

As at most schools, the past year at Crosstown has been a challenge for staff and students alike. “It’s not perfect, and we’re ready to get back [to in-person],” Terrill told us in February. “But as far as feeling like we had a wasted year, we do not feel that at all. There’s a lot of takeaways from this year that will be applied in the future.”

Spickler shared some examples: “Covid has given us some time and space to do some systems level work that we had not really done before,” like develop curriculum for advisory, or collaborate more closely across grade levels.

Systems change aside, the evidence that’s beginning to emerge on how students are faring at Crosstown in spite of the pandemic is not at all discouraging. Not only have attendance and retention been impressive, but meaningful academic outcomes are emerging, too: Crosstown juniors outperformed both the district and state on the ACT, averaging 20.1 as first-time test-takers.

“Word is out that we do a really great job with kids,” Terrill concluded, “whether it be in-person or virtual.”

Undergirding these success stories are the positive, trusting relationships Crosstown staff members have intentionally cultivated with students and the sense of ownership and agency students have developed because their teachers trusted them.

About This Series

This blog post is part of a larger series exploring the practices and success indicators used for student-centered learning in a pandemic—and beyond. We are grateful to the Leon Lowenstein Foundation for their generous support for this series.

Read More & See Other Posts