This post is part of a larger blog series this year, looking at how schools have used student-centered strategies to respond to the pandemic. This includes both learning designs, but also the success indicators schools use to know whether they are successful. Here, we go in depth on one area of success: student engagement.

Over the past few months, this series looked deeply at five student-centered schools from around the country. A common theme was the importance they placed on student engagement. Student-centered learning—with its focus on deep, applied learning of material relevant to students—requires not just passive attendance, but active and engaged participation.

So what is engagement, really? And how are schools defining, measuring, and acting upon this key concept, in a pandemic and beyond? Let’s explore.

Engagement in education research and public opinion

Researchers see engagement as multidimensional. It includes at minimum an emotional dimension (a sense of “belonging” and connection to school), a cognitive dimension (seeing value and relevance in what one is learning), and a more visible, behavioral dimension (attendance, participation, time on task, completing assignments, etc.).

Engagement matters: it’s consistently associated with outcomes like academic achievement, social-emotional development, and graduation from high school or college.

Engagement also matters to families. A lot. Per a nationwide PDK poll, 8 in 10 Americans believe that “how engaged students are in their classwork” is “very important” in measuring the effectiveness of schools—the highest of all other measures asked on the survey.

In practice, at the level of students and schools, engagement is tricky to track and measure. That became even more difficult in a pandemic, with students often learning in a physically distant space, and with some schools reporting up to a half of their students never signing in.

The remainder of this post explores specific strategies schools are using to do so with integrity.

The classics: attendance and retention

The most commonly used measures of engagement are student attendance and retention. Ginger Spickler, of Crosstown High, puts it powerfully: “Attendance and retention are huge. If you’ve got kids constantly leaving, clearly there’s not too much great to try to stay for.”

All of the student-centered schools we studied monitor both attendance and retention across time, to shape an overall understanding of how they were doing—and in some cases to offer support to specific students. Oftentimes that support is as simple as a call home from a teacher, checking in and expressing interest in the student if they haven’t been signing in to Zoom.

Asking students: check-ins and surveys

While attendance and retention are important, they aren’t enough to get at the depth of engagement required, especially for student-centered learning. Rebekah Kang of UCLA Community School shares, “We were really struck by how [attendance] didn’t capture engagement. I think the closest we’re coming is teacher observation… What does engagement mean? What does it look like? What does it sound like?”

Covid and distance learning have complicated these questions. While a student may be “in attendance” on Zoom it can be hard to tell where they’re truly at, especially if they have their screen off.

Several student-centered schools—including Crosstown and others who also measure attendance and retention—have adapted by placing extra emphasis on one-on-one student-teacher check-ins. These are both places to deepen their relationship with students, understand their interests, and shape their personalized learning experience. But those check-ins are also a place to capture a data point on engagement.

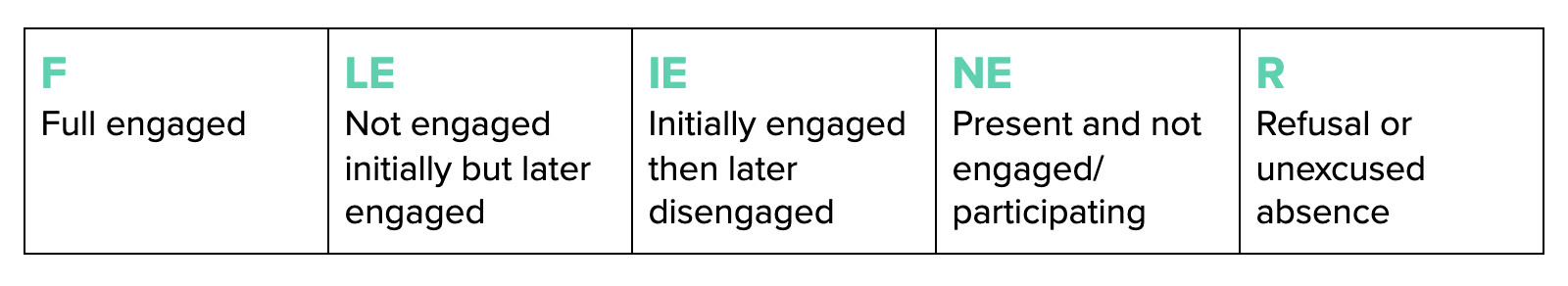

Johnna Noll, from Norris Academy, describes: “We created a dashboard that our staff use… After every adult was scheduled to meet with a learner they went on and did an assessment of that learner’s level of engagement during the session. We had five different levels of engagement they could select.” The dashboard is then used to identify students who may need social and academic interventions.

Another way to get at these deeper dimensions of engagement is simply to ask students: Do you see relevance in your work? Are you on task? Plenty of schools give student surveys, and they can surely be one useful tool. But they are only given once or a couple of times a year and often don’t give data that’s immediately actionable. The sorts of check-ins described above, and the data that come from them, solve that problem.

Engagement as deep, quality work

Student-centered schools commonly found one obvious way to gauge engagement: looking at student work itself.

Liana White, of West Hawaii Explorations Academy (WHEA), describes: “Until somebody turns something in, it’s not always possible to tell how engaged they are. You can’t tell what their level of work is or where they’re at with their work.”

This brings us full circle to the rest of this series, which looks at ways that student-centered schools collect evidence of student learning. This includes strategies like rubrics, portfolios, presentations, processes for student critical self reflection, and more as described in the profiles. These strategies allow students flexibility in how they document evidence of learning while maintaining high standards—and in so doing also capture evidence of engagement.

Looking at quality of work represents the ultimate shift, from engagement as an abstract idea, to engagement as doing deep and meaningful work.

Conclusion

Student-centered learning involves more than changes to learning experiences. It also requires a shift in how success is measured. Student-centered schools are doing this, including how they measure student engagement.

But for student-centered schools, it’s not only about authentically measuring engagement, or even about doing well on those measures. It’s about using data—on engagement and beyond—to drive decision making tailored to the individual students they serve.

And this focus on adaptive flexibility has proven especially critical in this turbulent and ever-changing period.

About This Series

This blog post is part of a larger series exploring the practices and success indicators used for student-centered learning in a pandemic—and beyond. We are grateful to the Leon Lowenstein Foundation for their generous support for this series.

Read More & See Other Posts